Dogs and children can be best friends – but there’s always a chance of misunderstandings. The goal of this guide is to teach parents why dogs sometimes bite, how to recognise dog body language, and how to keep your children (and dog) safe.

Every parent has felt that jolt of anxiety when a strange dog appears at the park.

Is he friendly? Does the owner have him under control? Will my child want to say hello – and should I let them?

This isn’t an idle concern. There are approximately 4.5 million dog bites each year in the United States (according to an early-2000s study by the CDC). These are often minor bites, but some can cause lasting damage.

While we’re often most anxious about stranger’s dogs, up to 70% of bites actually happen at home. This could be because parents and children feel comfortable around their own pets, so safety is taken less seriously.

Even a mild-natured dog can bite in a situation where it feels it has no choice though. Unfortunately, the way children show affection tends to create these situations. Hugs, rough play, and loud noises can all be stressful for a dog – especially if he feels trapped.

Of course, most dogs tolerate human behaviour. What if a child tries to play with a strange dog in the same way as his or her pet though? Or if play gets a little too rough and the dog feels threatened?

For this reason, it’s vital for every parent to understand why dogs bite and how to identify warning signs. Even more importantly, children should know when it’s safe to greet a dog and how canines like to be treated.

Quick Navigation

Section 1: Why Dogs Bite Children – And Why They Usually Don’t

Let’s start on a positive note: there’s no doubt dogs make brilliant family pets.

They are loyal, fun and can provide children with one of their closest companions. There’s even evidence that children with pets develop better social skills, stronger immune systems and reduced anxiety.

Many dogs are also amazingly tolerant of children’s behaviour. While it’s not fair to allow behaviour that makes them uncomfortable or stressed, dogs typically try to avoid biting humans.

So, the goal of this article is not to scare parents.

Instead, it’s to help you understand a dog’s feelings, behaviour and body language so you can teach your child how to stay safe.

The Most Common Reasons for Bites

Most dog bites don’t happen without warning or reason. They are more often a result of miscommunication between the dog and human.

To keep your child safe, you need to understand why dogs bite children – because most bites are preventable. Some common reasons include:

In most cases, children have good intentions when they interact with dogs. They want to give affection or play – and are just behaving as they would with a human friend.

The key thing to remember is that dogs and children speak fundamentally different languages. Here are some common examples:

- When a child wants to show affection, it’s normal to give a dog a hug. Many dogs feel trapped when hugged though – especially if it happens suddenly and without warning.

- When a child wants to play, she may take the dog’s toy so it can throw it. If this is the dog’s valued possession it might feel defensive when the toy is taken.

- When a child learns their beloved pet is ill or in pain, it’s natural to stroke and comfort him. After all, that’s what the child’s parents do when they are ill. The dog is likely to feel threatened and anxious though – and may bite if it wants to be left alone.

- When a child wants to snuggle with his cuddly friend, he might get into the dog’s bed. This may be seen as an invasion of the dog’s private space though.

In most cases, the dog will show clear signs of distress through its behaviour and body language. Nipping or a full bite is nearly always a last resort. Of course, children don’t know how to identify these signals unless they have been taught – so it’s important for parents to understand basic canine body language.

Dogs and children should not be left alone unsupervised. It’s impossible to actively supervise at all times, so create a separation area for the dog. This should be a positive space that the dog feels relaxed and comfortable.

Section 2: A Parent’s Guide to Dog Body Language

Dogs have a wonderfully rich and well-developed communication system.

Two well-socialised dogs can communicate regardless of breed, size or where they have been raised – which is impressive when you think about the difference between a Great Dane and Chihuahua!

The problem for us humans is that this language is almost entirely non-vocal (aside from the occasional bark, sneeze, snort, whine or growl). While we use words to communicate, dogs rely on their various body parts to signal how they feel. Many of these signals are subtle and can be difficult to notice at first.

Once you start looking for body language cues, however, you’ll be amazed at how often your dog is communicating his or her feelings. You’ll also get better at predicting what a dog is likely to do next. This is essential for safely interacting with dogs – and potentially picking up warning signals before a bite.

Body Parts Used for Communication

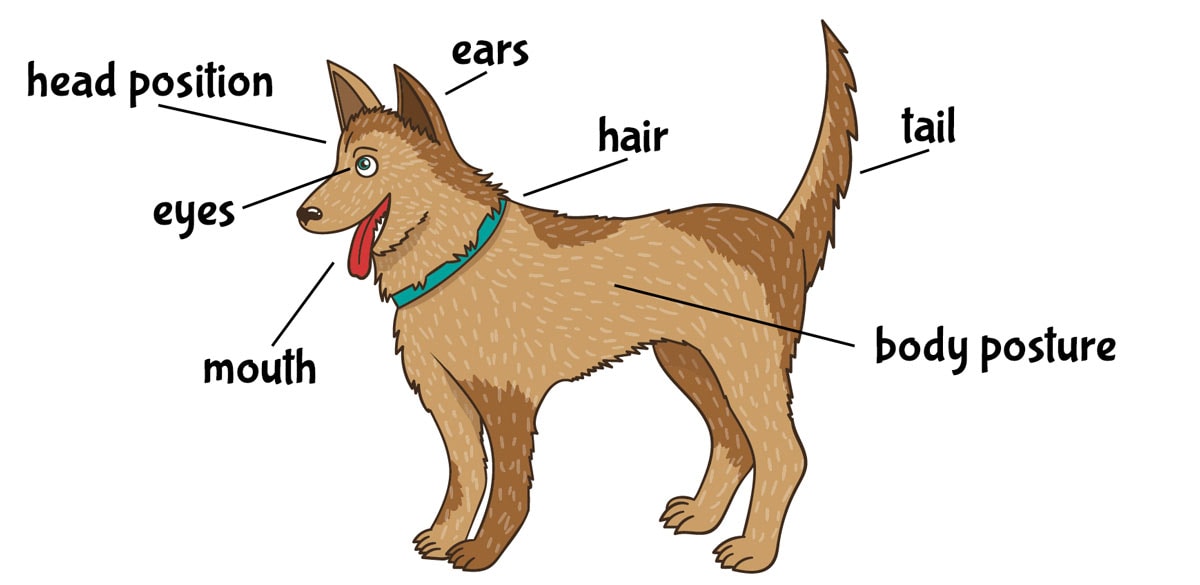

The key components of dog body language are the head position, ears, mouth, eyes, tail and body posture. A dog may also raise its back hair – the “hackles” – to show it’s upset or potentially aggressive.

As we’ll see in the following section, a dog uses multiple body parts to display an emotion. Here’s a quick overview of signals to look for though.

- Head Position. Whether the dogs head is turned away or towards something can show whether it wants to interact. The height of the head position can also indicate confidence in a situation.

- Ears. The shape and size of a dog’s ears affect whether they can be used for communication. For dogs that can use them, a natural ear position indicates comfort. Raising the ears can signal alertness or even aggression, while pulling back the ears shows friendliness. Flattened ears are a sign of fear or submission.

- Eyes. The most important part of the eye for communication is the white section (sclera). A tense or anxious dog may show more white than usual, while a relaxed dog may show little or no white. Dilated pupils may also signal a stressed or frightened dog, although this isn’t always easy to see.

- Mouth. An open mouth with a relaxed jaw often indicates a dog that feels comfortable. Some dogs also “smile” with their front teeth, which can be mistaken for aggression but is actually happiness when accompanied by a wagging tail, low head and flattened ears. If the mouth is closed, or if the dog is panting rapidly, this could indicate tension. Drooling without a food trigger, yawning or excessive lip licking can indicate stress or fear.

- Tail. When relaxed, a dog is likely to hold the base of his tail in a neutral position. As the dog gets excited or aroused – in either a positive or negative way – the tail tends to rise above the spine while wagging more rapidly. As we’ll see later in the article, however, a wagging tail doesn’t always indicate happiness. A scared dog often holds the tail between the back legs (it may still wag in this position even when the dog is fearful).

- Body Posture. Along with individual body parts, the overall body position can also hint at the dog’s emotion. A general stiffness in movement can show stress or discomfort, while exaggerated movements often indicate playfulness. If a dog is fearful, it’s likely to crouch, lean back or try to make itself as small as possible. Aggressive dogs usually stand tall with a tense body position and a slight forward lean.

Aside from body language, you should also consider behaviour. Is the dog moving towards or away from something? Does the dog appear frozen or is it continuing to move? The dog’s response to a person or object can tell you a lot about how it feels – even if the body language is difficult to understand.

If that sounds like a lot to remember, don’t worry! The next section shows how a dog combines these body parts to show common emotions, such as playfulness, fear or aggression.

How to Identify Common Emotions

A dog’s body language can show surprisingly subtle emotions, which is why even experts may struggle to understand every signal. As a parent, you don’t need to be an expert in canine body language though. Instead, focus on these five emotions: neutral, fearful, worried/anxious, playful and aggression.

Note: A dog’s breed can affect its body language. A stiff-eared Akita, for example, naturally has a different ear position to a cocker spaniel.

Subtle Signs a Dog Isn’t Happy

The five body positions above are easy to spot. They involve multiple body parts and there is often a clear target for the emotion.

In many cases, however, a dog will show a child more subtle body language when he’s anxious or stressed. These signals are designed to either appease the “threat” or to relieve stress.

Some examples to watch for when your child is interacting with a dog include:

- Turning head away from the child as a sign of appeasement

- Shaking to relieve tension

- Yawning when he’s not tired

- Licking lips when there’s no food around

- Walking away from the child

- Giving “whale eye” by showing the eye whites

- Body freezing until the “threat” moves away

- Crouching or crawling away

- Rolling over after moving away

- Placing head over a toy or other object

- Excessive panting (which is often mistaken for smiling!)

If you notice a dog showing these behaviours when interacting with your child, it means he/she isn’t comfortable with the current situation. While they don’t necessarily mean a bite is imminent, it’s probably time to end the interaction.

Even if you don’t think your pet will ever bite, it’s not fair to expect a dog to cope with behaviour that feels threatening or even rough. While it’s wonderful for a dog and child to develop a relationship, this must be built through positive interactions and trust.

On the other hand, here are some signs that the dog is relaxed, happy and wants attention:

- A relaxed facial expression

- Mouth held slightly open with a relaxed tongue (big dogs often let the tongue loll to the side when relaxed)

- Fast wagging tail

- Play bow to signal the next action is meant to be playful

- Exaggerated body movements

- Turning over for belly rub (this is not always a sign of submission!)

3 Body Language Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake #1 – A Wagging Tail Doesn’t Always Mean a Happy Dog

Many people think a wagging tail means the dog must be happy. This is often true, but dogs can also wag their tail for other reasons – such as arousal or frustration – so it’s important to look at other body language signals if you’re not sure.

A dog that’s wagging his tail between his back legs, for example, is probably feeling fearful or anxious. A dog with a tense body posture, fixed gaze and wagging tail, on the other hand, may be frustrated or defensive.

There’s also evidence that a happy and approachable dog will wag its tail more to the right. An unsure dog will wag more to the left.

Mistake #2 – Punishing a Dog for Growling

A natural reaction to hearing your dog growl at your child is to scold it. This is understandable, but a growl is the dog’s way to warn he’s not happy with the current situation. If he gets punished for growling, next time he may bite without warning.

Instead of punishing, calmly remove your child from the situation and try to work out what caused the growl. Was the dog showing signs of distress or frustration? Is he in pain? Or is he being defensive about an object or food? This can help you prevent the situation in the future.

Mistake #3 – Assuming Rolling Over is a Sign of “Submission”

There’s a common misconception that dogs only roll over when they are being “submissive.” Many people with dogs who love belly rubs would argue with this – and there’s now evidence to back them up.

Research has shown that body language in “play” mode may have different meanings to when the dog isn’t playing. So, while a while in some situations a rollover can show fear or appeasement, a relaxed dog may do it for different reasons. When with a person it trusts, it may just want you to rub its belly!

The key point here is that many behaviours can mean different things depending on the situation. This can make understanding your dog more confusing, but shows how rich and well-developed canine body language really is. To learn more about this topic, read our guide to why dogs roll on their back.

Section 3: How to Supervise Safe Play Between Children and Dogs

As I explained in the previous section, dogs and children often mis-understand each other. Common signs of a child’s affection, such as hugging, kissing or wrapping the dog in a blanket, can feel threatening. And the signs of discomfort dogs use to show they feel threatened usually aren’t recognized.

In some cases, this can lead to a warning growl or bite. Even “good” dogs with high tolerances may bite if they feel they have no other choice.

This isn’t the dog’s fault, nor is it the child’s. Both are acting with good intentions – it’s just they are having trouble understanding each other.

For this reason, it’s essential to supervise your child when he or she is interacting with a dog. This includes both strange dogs and your own pets. Just being in the same room isn’t enough though – you need to actively supervise.

Active Supervision at All Times

It’s a surprising fact that many dog bites are from a child’s pet (rather than a strange dog) and occur when a care-giver is nearby.

This usually doesn’t mean the dog has bitten without warning though. There are nearly always signs of discomfort, such as trying to move away, excessive lip licking, shaking, a lowered tail or turning the head away.

These signs are often missed. Sometimes they are even mistaken as positive reactions to the child’s attention.

For this reason, it’s essential to actively watch your child’s interaction with a dog and look for these signals.

If you notice signs of discomfort, you should intervene calmly but quickly. Allow the dog to get away from the situation so it doesn’t feel trapped.

You also need be proactive in recognising potentially negative situations. A good example is if you see a child walking towards a dog who is asleep in his bed or crate.

I also want to emphasise that dogs and children should never be left alone without supervision. The dog’s breed or temperament doesn’t affect this rule.

Plan How You Are Going to Supervise

Proper planning is vital when supervising young children and dogs. Jennifer Shryock provides a useful checklist for parents with new babies or toddlers, which I’ve paraphrased below:

- When the child and dog are in the same room and not separated by a physical barrier, is someone present and watching at all times?

- Do you have a plan for if there is a distraction or emergency (such as a delivery or phone call), so that the child and dog are not alone without supervision? If you need to go out to the car or stir something cooking on the hob, it’s best to physically separate the child and dog as bites can happen quickly.

- Is the person supervising giving the child and dog his/her full attention? Or are they distracted by the TV, mobile phone or laptop? Supervising can be mentally taxing, so it’s a good idea to take turns.

- Is the supervisor actively looking for signs of discomfort, aggression, stress or other warning signs in the dog or child? Or are they just reacting to negative situations when they arise?

Create a Positive Separation Environment

Having a place you can separate your dog and child is essential. It’s impossible to actively supervise at all times, so even a simple stair gate can provide some relief.

The key is to make separation a positive time for the pet and never use it as a punishment. The goal is to give your dog a place he can feel relaxed, not stressed for different reasons.

A separation environment is also useful if your child (or a visitor) is nervous around dogs. Screaming or crying can make a dog think the child is excited and wants to play, which can make things worse.

This doesn’t mean the dog should be shut in a small space for hours each day. It’s important for all dogs to learn how to feel relaxed when spending time alone though.

Here are some tips for making separation a positive experience:

- Try to create positive feelings around separation. A chew or tasty stuffed Kong can be a good way to create this association.

- When your dog is in his “safe space,” make it a house rule that he isn’t disturbed. That means no playing with him through the stair gate!

- If your dog doesn’t like to be separated, keep the periods short to begin with while making each time a positive experience.

- A sleeping dog should never be disturbed, even if he isn’t separated. Constantly being woken can cause a dog to become frustrated and over-tired.

Be Extra Cautious When Supervising Other Children

Just because your dog tolerates certain behaviour from your children doesn’t mean he’ll react the same to their friends.

Other children may also not know how to behave with dogs. If they haven’t grown up with dogs, they might not understand why rough play or “wrestling” isn’t appropriate.

For this reason, you should be extra careful when supervising your child’s friends. It’s often a good idea to put the dog in a separate room before they arrive, so he can get used to the noises before meeting them.

It’s also important to set ground rules when the child arrives. These can include:

- Not approaching the dog when he’s eating, in his crate or bed, unwell or sleeping.

- Being gentle with the dog and avoiding rough play, such as wrestling.

- Not taking one of the dog’s toys.

- Not playing with the dog in an enclosed space, such as under a table.

- Never surprising or sneaking up on a dog.

Don’t Judge Behaviour by Human Standards

While a child hugging a dog might look cute, it can feel threatening and overwhelming to the animal.

It often looks adorable when a child hugs or kisses a dog. Even if you know dog body language and signs of discomfort, it can be hard to accept that many dogs just don’t like this type of affection.

That doesn’t mean all dogs will eventually bite if hugged. Some dogs will put up with hugs and kisses – and some may even enjoy it.

If your dog is showing signs of stress or anxiety, however, it’s important to explain to the child that the dog doesn’t like it. This could potentially prevent a bite and helps your dog to feel more relaxed.

As I mentioned earlier, even if a dog tolerates being hugged or other boisterous behaviour, it’s unfair to expect it to handle this regularly.

It’s also essential to teach your child how dogs like to be stroked or petted. Which leads me nicely into the final section of the article.

Section 4: Teaching a Child to Safely Interact With Dogs (Without Causing Fear)

Along with supervising your child and dog, it’s also important to teach your child how to interact safely with canines.

This needs to be approached in a positive way though. You don’t want your child to fear dogs, but they need to learn to respect them.

Some obvious examples include not hitting, teasing or startling a dog – and most parents teach their children these basic rules. But does your child know when a dog should be left alone? Or how to politely greet a dog once given permission to do so? If not, here are some simple lessons every child should know as soon as possible.

1. Teaching a Child When It’s Acceptable to Interact a Dog

I’ve been at friend’s houses where the children regularly jump on their pet dog when he’s trying to sleep. I’ve even seen children purposefully startle a dog to see its reaction.

I don’t blame the children for this – they are simply treating the dog as they would a human family member.

It highlights a common problem though: many children don’t know when it’s acceptable to play with a dog.

In these households, the dog is expected to be happy to play at all times. It’s also expected to be approachable and friendly regardless of the situation. This isn’t realistic or fair on the dog.

For this reason, try to teach your child that there are times when a dog should be left alone – especially when:

- Sleeping. Dogs can become frustrated when woken. Being suddenly disturbed can also startle the dog, which may lead to a reflexive bite.

- Eating. Dogs are often possessive of their food. While food aggression is something that should be addressed, a child should still be taught to never approach a dog when he’s eating (including chews or bones).

- In a Safe Space or Enclosed Area (such as a crate). Behaviour that a dog may tolerate in an open space may feel more threatening when he/she can’t escape. Teach your children to avoid the dog when he’s in his bed, under a table or in a crate.

2. Teaching a Child How to Politely Greet a Friendly Dog

You shouldn’t reach over a dog’s head (as in the photo above) when first greeting a new dog.

As any dog walker knows, many parents are happy for their children to approach a strange dog without warning or permission.

I’ve had children run up to my dog while playfully screaming, before patting her on the top of the head and running off. The parents never asked if the dog was safe to approach. They didn’t even say hello!

Fortunately, most dogs (including mine) are tolerant of human’s strange behaviour – but some dogs aren’t willing to accept boisterous behaviour from a stranger. If a child accidentally scares a dog, there’s a chance it could get bitten. The dog is also likely be blamed even though it was stressed or anxious.

For this reason, teaching your child how to safely and politely approach a dog is really important – both for your own pets and any you meet in public locations. Here’s a simple five step process:

- The first step is to teach your child to never approach a dog until you have given them permission. You should also always ask the owner if your child can meet the dog. If the owner isn’t around, such as if the dog is tied up outside a shop, leave it alone.

- Once the owner has given permission and you have told your child it’s OK, they should approach with their arm out and hand in a fist. This prevents a dog biting the fingers, which is unlikely but it’s best to be safe.

- Your child should hold the fist low enough for the dog to sniff. If the dog continues to look at the hand or licks it, he’s communicating that he’s happy to be greeted. If he looks away or walks off, he would rather be left alone.

- Once the dog has given permission to be greeted, the child can start to stroke him on the shoulder or chest. If the dog is showing positive signals, a back scratch is also acceptable. Avoid the head and face.

- As soon as the dog starts showing any of the “discomfort” signals listed above, ask your child to move away from him.

This might sound restrictive – but it’s a much safer way to approach a dog for both your child and the animal. In my experience, many children also love to learn how to “talk doggy.”

3. Teaching a Child to Recognise When a Dog Has “Had Enough”

Canine body language can be confusing even for experts, so it’s difficult for young children to understand subtle signals.

With that said, teaching your child to recognise when a dog doesn’t want to play anymore is always a good idea. The most important signals include:

- If a dog looks away or lowers his head, the child should know he probably doesn’t want to interact.

- If a dog tries to walk or run away, the child should know not to follow or chase.

- If a dog growls, the child should know to move away and stop whatever she/he was doing.

Of course, you should be actively monitoring your child at all times when with a dog. But teaching the basics can reduce the dog’s stress and help keep your child safe.

Summary

Children and dogs make wonderful companions. They can form lifetime bonds that are enriching for both the pet and human, while also teaching social skills, compassion and how to care for an animal.

With that said, dogs and children don’t always speak the same language! Our canine friends aren’t born knowing human body language and how we show our love. Children may also instinctively treat beloved pets like a human by showering them with affection or games.

These differences mean it’s no surprise there are often mis-understandings. Many dogs will be tolerant of “weird” human behaviour, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t stressed or anxious. Some dogs may also feel forced to resort to biting – often after numerous canine signals have gone unnoticed.

For this reason, it’s vital for parents to understand the basics of canine body language and how dogs like to be treated. By actively supervising and teaching children how to politely interact with dogs, you can reduce the chances of a bite and help create stronger bonds based on trust.

Further Reading and Resources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18836045

- https://nspt4kids.com/parenting/how-dogs-help-children-develop-social-and-emotional-skills/

- https://www.bluecross.org.uk/pet-advice/be-safe-dogs

- https://pets.webmd.com/dogs/dog-body-language

- https://www.aspcapro.org/resource/7-tips-canine-body-language

- https://www.whole-dog-journal.com/issues/14_8/features/Canine-Body-Language-Defined_20325-1.html

- https://yourdogsfriend.org/life-with-dogs/children-dogs/

- http://www.pawsacrossamerica.com/interpret.html

- http://www.silentconversations.com/introduction-to-dog-body-language/

- http://www.scanimalshelter.org/sites/default/files/Canine_Body_Language_ASPCA.pdf

- https://positively.com/dog-training/understanding-dogs/canine-body-language/

- http://animalbehaviorassociates.com/blog/supervising-pets-children/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/canine-corner/201501/rollovers-do-not-always-mean-dog-is-afraid-or-submissive

- https://www.petful.com/behaviors/how-to-greet-strange-dog/

I have read a lot of your dog information/ articles, especially this one. Actually learned some things that even someone like me; grew up with dogs; have had one my whole life; always friend them when I see one etc, …but was wondering, Do you have a specific book/ article on bringing home baby with dogs”? My son and his wife are expecting twins in a week or so. I have been trying to tell them how important it is to prepare their two dogs for the bringing home TWO BABIES!!

The dogs are fairly good natured, however, both are breeds that, I KNOW from personal experience (raised 5 children around a Chow-Chow) I am trying to find a short read on this, obviously time is of the essence. Thank you for your time, would appreciate any info, even if just a quick email. Thank you and have a Merry Christmas and a wonderful New Year

Marianne

Hi Marianne. You’re right that it’s certainly important for them to prepare. Firstly, they should have a plan for the dogs when they go into labour (who will look after them, where will they stay etc). There are some changes they may want to start getting the dogs used to, such as new sleeping arrangements, walking next to a pram, and possibly varied walking times if the dogs are used to a very rigid routines. Get the dogs accustomed to some of the changes now before the twins arrive! Stocking up on chews, stuffed kongs, puzzle toys etc will also be useful to keep the dogs entertained during busy times.

I’ve heard good things about a book called “Hey Dog! Sniffs are for Feet!” by Wendy Keefer. It’s a relatively new book so I haven’t had a chance to read it yet, but it’s for parents who need to introduce a small child to a dog (or vice versa), so it might be worth looking at.

Hope that helps!